Residential Proxies, Friend or Foe?

Residential proxies are increasingly coming under scrutiny, drawing attention to the methods by which their IP addresses are obtained and their varied uses. They underscore the substantial reliance on GeoIP information for a range of online services, such as content customisation and cybersecurity measures.

Rising awareness about these proxies presents a complex and layered reality. They offer solutions to businesses, researchers, and individuals seeking anonymity or looking to bypass GeoIP-dependent restrictions. Yet, the use of residential proxies simultaneously arouses ethical dilemmas, largely due to the potential for misuse.

In this exploration, we'll shed light on what residential proxies are, how they function, their advantages, and the ethical questions they raise. From their purported benefits to their darker implications, residential proxies warrant a deep and nuanced understanding.

Demystifying Residential Proxies

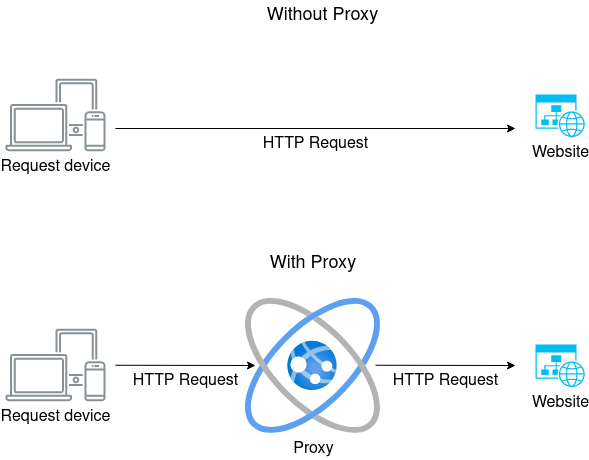

These proxies function by connecting automated software to the internet via IP addresses tied to real-world residential locations. This method allows these software tools to simulate genuine internet usage, offering a way to bypass geographical and network restrictions while providing an added layer of online anonymity.

It's essential to clarify the legal and ethical issues associated with residential proxies. While their use can be entirely within the bounds of the law, such as for web scraping and data gathering, they often facilitate activities that, although legal, may infringe upon the intended usage policies of certain online services. This could include mass consumption of data intended for general use, such as scraping websites for machine learning datasets. These actions, although not strictly illegal, raise substantial ethical questions and are often unwelcome by the data providers.

Delving into the Applications of Residential Proxies

The unique characteristic of residential proxies, which allows requests to appear as if they originate from local, residential networks, facilitates a range of valuable applications. This features enables a large number of use cases, including:

-

Concealing True IP Addresses: Residential proxies enabled third parties with the ability to hide genuine IP addresses and location, obscuring their true identity. By routing internet traffic through residential IP addresses, they can evade detection, circumventing security rules and accessing geo-restricted content.

-

Research and Monitoring: Residential proxies are often employed by researchers, analysts, and market intelligence professionals to assemble data and keep a watch on online activities. By utilising residential IP addresses, they can emulate real user ip addresses, bypassing restrictions.

-

Web Scraping and Data Gathering: The role of residential proxies in web scraping and large-scale data collection is pivotal. With the capacity to rotate IP addresses and access a wide range of residential locations, third parties can scrape valuable data from websites without setting off anti-scraping measures. Residential proxies facilitate discrete data scraping, ensuring unimpeded access and precise results.

-

Ad Verification: Residential proxies are extensively utilised for ad verification purposes. Ad verification companies utilise residential IP addresses to confirm the accuracy and legitimacy of online advertisements. By mimicking genuine residential connections, they can ascertain that ads are correctly displayed and monitor the performance and integrity of advertising campaigns.

-

Ad Fraud: Residential proxies also carry the risk of being used maliciously to perpetrate ad fraud. Competitors or their agents may utilise residential IP addresses to falsely inflate the views of a rival's online advertisements. By using genuine residential connections, these entities can manipulate advertising metrics, compromising the accuracy and integrity of the ad's performance data. This abuse of residential proxies for inducing ad fraud poses a significant concern for the online advertising industry.

-

Last Mile Monitoring: Last mile monitoring is another application where residential proxies are used, permitting companies to assess the user experience from a residential viewpoint. By using residential IP addresses, they can monitor website loading speeds, test service availability, and evaluate the performance of online platforms accurately. This enables organisations to pinpoint and rectify issues that may negatively affect user satisfaction.

Navigating the Risks and Concerns

Navigating the risks and concerns associated with residential proxies is crucial, as their utilisation can introduce significant limitations and potential security vulnerabilities, particularly when users are unaware they are hosting one.

Despite their valid uses, residential proxies can be manipulated for cybercriminal activities. Malevolent actors may exploit residential proxies for account takeovers, committing fraud, or other targeted attacks.

The utilisation of residential proxies without the knowledge or consent of residential users brings about serious security issues. These users, unaware of how their connections are being utilised, could face potential legal repercussions, compromised privacy, and exposure to cyber threats. Their devices could unwittingly participate in malicious activities, making them susceptible to legal consequences and reputational damage.

Exploring the Creation of Residential Proxies and their Implications

Residential proxy providers acquire their proxy networks through various means, some of which can have significant security implications.

Providers can procure residential proxies via partnerships with Internet Service Providers (ISPs) or by leasing IP addresses from legitimate residential users. However, it's important to be aware that some providers or private groups may resort to questionable practices to obtain residential proxies.

-

SDKs: Certain applications may incorporate Software Development Kits (SDKs) that gather and sell user data, including their IP addresses. In some instances, these SDKs can be exploited by residential proxy providers to acquire residential IPs without the explicit consent or knowledge of the users.

-

Malware Exploitation: Malware such as botnets can infiltrate the devices of unsuspecting residential users. Attackers may then exploit these infected devices as part of a broader residential proxy network, without the awareness of the users. This unauthorised use of residential IPs poses significant security threats to both the affected users and the wider internet ecosystem.

-

Free VPN Services: Some free Virtual Private Network (VPN) services, which promise anonymity and privacy, might actually utilise users' connections as part of their residential proxy networks. Users unknowingly become exit nodes for other users' internet traffic, potentially exposing their connections to malicious activities.

The practice of using residential proxies without the knowledge or consent of residential users raises serious security concerns. These users are oblivious to how their connections are being used, which can lead to potential legal consequences, compromised privacy, and vulnerability to cyber threats. Their devices might unknowingly participate in malicious activities, exposing them to potential legal consequences and reputational damage.

The birth of 'ethical' proxies

An important dimension to the discussion surrounding residential proxies involves the birth of providers claiming that their IP address pools are ethically sourced. These companies argue that they have obtained the consent of the original IP owners and provide transparency in how these connections are utilised. By positioning themselves as 'ethical' residential proxy providers, they aim to mitigate the associated risks and concerns.

However, even if consent is obtained, the potential for misuse remains a significant issue. This is largely due to the inherent anonymity of residential proxies and the difficulty of tracing activity back to the original user. Despite these claims of ethical sourcing, the complexity and opaqueness of the residential proxy environment mean that it remains a grey area, inviting scepticism and demanding further scrutiny.

It is clear that the dialogue around residential proxies is nuanced and layered, and it's essential for consumers, providers, and regulators to have a thorough understanding of these dynamics as the digital landscape continues to evolve.

From Hola VPN to the Camaro Dragon: Unveiling Residential Proxies

Let's dive into some publicised incidents that shed light on the formation of residential proxies and the impact they have had on the industry and users. These examples illustrate the diverse ways in which residential proxies can be created and utilised, both legitimately and otherwise.

-

Hola VPN is a well-known free VPN service that pledges to provide privacy, security, and access to blocked content. However, it fell under scrutiny when it was revealed that it was selling its users' bandwidth to its sister company, Luminati, which operates a residential proxy network. Essentially, users of Hola VPN unknowingly became part of a residential proxy network, with their connections being utilised by third parties. This raised significant ethical and security concerns as users' devices could be implicated in any illegal activities carried out using their IP addresses.

-

The residential proxy service known as 911 has been selling access to hundreds of thousands of Microsoft Windows computers for the past seven years. This service enables customers to route their internet traffic through these computers, allowing them to appear as if they are browsing from any country or city around the world. While 911 claims that its network comprises users who voluntarily install its "free VPN" software, recent research indicates that the proxy service has a history of obtaining installations through shady "pay-per-install" affiliate marketing schemes, some of which were operated by 911 itself. The service primarily targets users in the United States but has a global user base. Residential proxy networks like 911 can serve legitimate business purposes, but they are often abused for cybercriminal activities due to the difficulty in tracing malicious traffic back to its source.

-

Cybercriminals are increasingly leveraging residential broadband and wireless data connections to anonymise their malicious traffic. One notable type of network, referred to as "bulletproof residential VPN services" has gained attention. These networks are constructed by acquiring discrete blocks of internet addresses from major internet service providers (ISPs) and mobile data providers. An investigation into one such company, Residential Networking Solutions LLC (also known as Resnet), unveiled that it had obtained a significant number of IP addresses, some of which were previously controlled by AT&T Mobility. Resnet leased these IP addresses, enabling it to resell data services for major providers such as AT&T, Verizon, and Comcast Cable. However, the precise nature of the relationship between Resnet and AT&T remains unclear, and the matter has been referred to law enforcement. Instances like these emphasise the potential abuse of IP addresses within residential proxy networks.

-

Infatica.io, a Singapore-based company, has developed a network of over 10 million web browsers that clients can rent to conceal their true internet addresses. The company achieved this by compensating browser extension developers to incorporate its code into their extensions. Many extension developers struggle to earn fair compensation for their work, making offers like these enticing. Infatica seeks extensions with at least 50,000 users and offers to pay developers between $15 and $45 per month for every 1,000 active users with the code included in their extensions. Infatica's code routes web traffic through the browsers of extension users, providing anonymity to the company's customers. The service's pricing depends on the volume of web traffic a customer wishes to anonymise. However, this approach raises concerns about privacy and the potential misuse of users' browsers for malicious activities. Developers, particularly those who author free software, can find the monetisation opportunity offered by residential proxies extremely tempting. The potential to earn revenue from their existing user base by incorporating such code into their extensions can present a persuasive proposition.

-

Camaro Dragon, a form of malware, provides a recent example of residential proxies being acquired through more malicious means. This malware infects the devices of unsuspecting users, forming a botnet that can then be utilised as a residential proxy network. Infected devices can then be exploited for various cybercriminal activities without the knowledge or consent of the device owners. This example highlights the significant cybersecurity risks associated with residential proxies and emphasises the importance of robust protection measures.

-

Volt Typhoon, a state-sponsored actor based in China that typically focuses on espionage and information gathering. Volt Typhoon proxies all its network traffic to its targets through compromised SOHO network edge devices (including routers). Microsoft has confirmed that many of the devices, which include those manufactured by ASUS, Cisco, D-Link, NETGEAR, and Zyxel, allow the owner to expose HTTP or SSH management interfaces to the internet. Volt Typhoon has been active since mid-2021 and has targeted critical infrastructure organizations in Guam and elsewhere in the United States.

These examples serve as compelling illustrations of the ethical, security, and legal issues surrounding residential proxies. They underscore the significance of transparency and consent in their acquisition and usage. The implications for users, the security industry, and the broader digital landscape are substantial, emphasising the need for stricter regulations, user education, and responsible practices to ensure the protection of users' privacy, security, and the integrity of the internet as a whole. It is crucial to address these challenges and find effective solutions to mitigate the potential risks and misuse of residential proxies.

Unveiling the Legal Consequences of Residential Proxies in Data Scraping Operations

Residential proxies are a topic of concern due to their potential for misuse and legal implications. Two notable cases, the Ticketmaster Case and the Meta vs Bright Data Case, have brought attention to the significant challenges posed by the unauthorised use of residential proxies in commercial settings and data scraping operations. These cases serve as cautionary tales, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding of the potential legal ramifications surrounding the use of residential proxies in real-world scenarios.

-

The Ticketmaster Case: In 2018, a major international case came to light when Ticketmaster sued Prestige Entertainment for using residential proxies to circumvent ticket-purchasing limits and scoop up large amounts of tickets for resale. This case underscores the potential misuse of residential proxies in commercial settings, and how they can be used to breach the terms of service of websites.

-

The Meta vs Bright Data Case: The legal case between Meta Platforms, Inc. (formerly Facebook) and Bright Data Ltd. demonstrates a contentious and potentially unlawful use of residential proxies in the real world. In this case, Meta accused Bright Data of operating a business designed to use automated software for the purpose of scraping and selling data from various online platforms, including Facebook and Instagram. This scraping was allegedly facilitated using unauthorised tools and services that bypassed detection by Meta's security measures. Despite Meta's efforts to halt these activities, Bright Data purportedly continued its operations. The data involved included user profiles, follower counts, and shared posts. Bright Data was alleged to not only scrape this information but also advertised the sale of the scraped data. The scope of this operation was extensive, with the Instagram data set alone priced at $860,000.

These examples can help paint a more complete picture of the many ways in which residential proxies are used in practice, the challenges they present, and the controversies surrounding their use.

Pondering the Wider Implications for the Security Industry

The expansion of residential proxies and their acquisition through potentially unsound methods has larger implications for the security industry. It brings into question issues around transparency, ethical practices, and the responsibility of proxy providers.

-

Ethical and Regulatory Implications: The questionable practices some providers use to acquire residential proxies highlight the need for stricter regulations and industry standards. This would ensure that residential proxies are obtained and used in a lawful and ethical manner, protecting users' privacy and the wider internet ecosystem. There is a clear demand for more transparency in how these services operate and procure their proxies.

-

Cybersecurity Implications: Residential proxies can serve as a catalyst for malicious cyber activities, ranging from fraud to targeted attacks. This can lead to an increased need for cybersecurity measures and protections, potentially reshaping strategies and priorities within the cybersecurity industry.

-

Legal and Reputational Implications: With individuals unknowingly becoming part of a proxy network, there could be legal repercussions for them if their connections are utilised for malicious activities. This could potentially lead to greater scrutiny and liability for companies operating within this space.

-

State Actors and Residential Proxy Networks: The fact that state-sponsored actors have been known to establish their own residential proxy networks within foreign countries for various campaigns, including information warfare, disinformation campaigns, and surveillance, adds another layer of complexity to the issue. These activities pose significant geopolitical and security risks, necessitating increased international cooperation and robust defense mechanisms.

The rise of residential proxies has shone a spotlight on a key issue in our online world - the problematic premise of trusting residential and mobile IPs and the use of GeoIP as a reputation or security measure. The widespread use of these proxies has shown that service providers have become overly reliant on GeoIP data, which has in turn created a myriad of complexities and potential for misuse.

The fact that these proxies can be obtained from uncertain or even unethical sources further muddies the waters, putting the trustworthiness of our online interactions into question. This can make navigating the digital landscape more challenging, and can also introduce security risks.

Residential proxies aren't just tools; they highlight a significant issue in the way we approach digital access and security. Understanding what we already know, questioning current practices, and seeking new solutions are vital steps in creating a digital world where residential proxies are used responsibly and ethically. Recognising the false sense of security GeoIP restrictions provide is a part of this journey.

As we conclude Part 1 of our series on residential proxies, we prepare to delve deeper into a specific case in Part 2: the Camaro Dragon malware. This sophisticated malware employs residential proxies in a way that exemplifies their potential for misuse. Stay tuned as we unpack the workings of Camaro Dragon, its impact on cybersecurity, and how you can safeguard against such threats. Make sure to read on and stay informed.

-

Mi, X., Tang, S., Li, Z., Liao, X., Qian, F., & Wang, X. (2021). Our Phone is My Proxy: Detecting and Understanding Mobile Proxy Networks. Retrieved from https://xianghang.me/files/ndss21_mobile_proxy.pdf ↩

-

Mi, X., Feng, X., Liao, X., Liu, B., Wang, X., Qian, F., Li, Z., Alrwais, S., Sun, L., & Liu, Y. (2019). Resident Evil: Understanding Residential IP Proxy as a Dark Service. Retrieved from https://www-users.cse.umn.edu/~fengqian/paper/rpaas_sp19.pdf ↩

-

Krebs, B. (2019, August 19). The Rise of "Bulletproof" Residential Networks. Retrieved from https://krebsonsecurity.com/2019/08/the-rise-of-bulletproof-residential-networks/ ↩

-

Krebs, B. (2022, July 18). A Deep Dive Into the Residential Proxy Service '911'. Retrieved from https://krebsonsecurity.com/2022/07/a-deep-dive-into-the-residential-proxy-service-911/ ↩

-

Krebs, B. (2021, March 1). Is Your Browser Extension a Botnet Backdoor? Retrieved from https://krebsonsecurity.com/2021/03/is-your-browser-extension-a-botnet-backdoor/ ↩

-

Meta Platforms, Inc. v. Bright Data Ltd. Retrieved from https://unicourt.com/case/pc-db5-meta-platforms-inc-v-bright-data-ltd-1374026 ↩

-

Volt Typhoon targets US critical infrastructure with living-off-the-land techniques. Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/05/24/volt-typhoon-targets-us-critical-infrastructure-with-living-off-the-land-techniques/ ↩